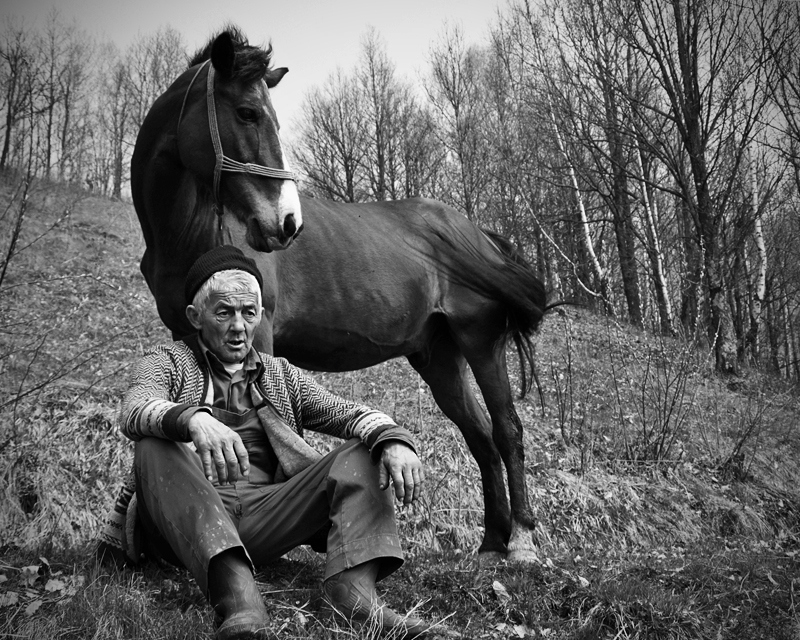

“I’ve often said there’s nothing better for the inside of a man than the outside of a horse.” – Ronald Reagan

The horse. Constant companion, steadfast in war and exploration, faithful through deserts and storms. The galloping hooves of one, a resounding valiance piercing the silence of the windswept plains. The thunderous hooves of many, an oncoming torrent of overwhelming power and force. A ceaseless source of legend, transcending cultures and time as one of mankind’s most cherished and storied animals. And the current pain in my ass.

A few days before our trek began, I had come across an old proverb: If a man wishes to see into his soul, he need only look at his reflection in the eye of his horse. “Well shit,” I think as I bounce roughly up and down on my saddle, “What does that make me?” My horse continues his open rebellion for a third straight day, trotting along while all others enjoy a gentle walk along the grassland. I attempt to slow him down and he halts instead, falling behind our group. I sigh and yield… and we’re back to trotting; mocking and taunting my lack of confidence, jarring my lower back, chaffing my already-raw backside. “He knows what he’s doing,” I grit through my teeth, “My horse is a sadist.” If he is a reflection of who I am at my deepest, he’s made me well aware that, as far as he’s concerned, I’m a far cry from the knights, cowboys, and cavalrymen that have come before me.

For all my frustrations, I have no real right to be upset. I’m at the Chilean tip of the Americas, galloping freely over Patagonian lands that would make even the most experienced National Geographic photographer blush from the surrounding beauty. I can’t help but think Tolkien would stand aghast at his Middle Earth vision come to life if he could have seen the red sun kissing the Cordillera del Paine in the not-so-distance as it does now. The land here has an unspeakable richness, a brutal splendor. Much like my nana’s wedding band or the eyes of our few remaining World War II veterans, the very rocks of this harsh place silently, boldly emit some deeper wisdom, of having seen and known. Before my rapture can culminate, I’m brought back down to earth by Hail, my appropriately named form of transportation. He’s decided we’re going to cantor now. I’m at the end of the world and my horse hates me.

As we ford a swollen river, my anger intensifies, less at the horse than myself. The horse doesn’t respect me. How can I assert myself? What am I doing wrong? Everyone else seems fine. I’m not in control. The self-flagellation begins to take a different route as it bleeds into more than horsemanship. I’m not worth respect. I have no clue how to assert myself with women. I do everything wrong. Everyone else seems fine. I’m not in control. I find myself fighting back a bevy of emotion as we make our final approach to a sheep estancia for a late lunch. I spur Hail into high gear – if we’re to trot, might as well let him gallop and get me off his back all the quicker. I dismount (sweet relief!) and head into the barn with the others, but not before throwing one final glare at Hail. He stares right back, his judging eyes defiant.

While lunch is being readied, we’re shown the grounds and given the history of the estancia by one of the gauchos and his fifteen-year-old son, Matias. We make our way through the just-used slaughterhouse and are surprised to find a ping-pong table set in the midst of the intestines and wool. The teenage shepherd strikes up a game with one of our group and proceeds to eviscerate him with the meanest serve this side of Forrest Gump. Besides the sheer wonder of standing in a Patagonian slaughterhouse watching a game of ping pong between individuals who speak different languages, I’m captivated by Matias’ confidence. He has a security amongst this company of men, stands upright, knows the strength of his hands, the force of his voice. The others count him as an equal and treat him as such. How is it that someone years younger has already realized such a way of life?

These thoughts linger through lunch and into teatime, a tradition amongst gauchos harkening back to their European heritage. We gather in the ranching house, a simple one-room building with benches lining the walls and an old wood stove in the center. As we settle in, our hosts begin to prepare the concoction, placing the herbs into a hollowed gourd and filling it with hot water. The gourd is then passed around from one man to the next, a fellowship amongst cowboys not too unlike a peace pipe. As we drink, we share stories and laughs back and forth, growing far closer than our stilted Spanish and their poor English should allow, warmth coming from tea and kinship alike. As I drink in the moment, I grasp there is a unique simplicity to the way of life at this edge of the continent, not saccharine or quaint, but whole. Content. A day’s hard labor counted a blessing, the caring arms of loved ones upon their return, a gift. The land is unforgiving, the sun rarely coming far past the horizon line, wind biting into your core, the cold chasing you in your sleep. Every day is a balance of testing and joy, being pushed to the limits of self while fighting for inner warmth. It strikes me that this is what has enabled the strength I see in Matias, this quiet confidence. He knows his weathered hands because the land has required it of him, his resounding voice because the herder must herd. There is worth in the elements, in the testing. These forces craft character, like water smoothing stone over time, drop by drop.

As we make to leave and begin saddling up, I look at Hail in a different light. Not as a threat or an enemy, but as the gift he is, an opportunity to deepen who I am. I swing up into the saddle and trot over to the others in the group. I realize I have gotten used to his ways, adjusted how I sit in the saddle, even improved as a rider. Matias notices Hail’s trot and walks over with a Cheshire grin, flagging our guide to translate. “He says you were given a shepherd’s horse.” I look from the guide back to Matias, confused. “What does that mean?” I ask. “They are trained never to walk, only to run or trot. Better for herding.” I look back in pure astonishment. Of course. Of course Hail’s a shepherd’s horse. He begins to chuckle, perhaps from the look of complete bewilderment on my face. Before I realize it, I’ve joined him and we devolve into a fit of laughter. All the pressure I was placing on myself, all the frustration over what was ultimately out of my control, all utterly cast aside. I shake my head. Matias rubs Hail’s neck and looks up at me. “You ride this horse, now you are one of us, no?” he says in his best English. He offers his hand. I shake it and nod. “Me siento honrado.”

Written by: Madison Ainley